Multiplexing Channels in Go

Write simpler concurrent algorithms for fun and profit

Here I will provide some context on how the concept of multiplexing (or joining) channels got into my life, how it changed how I design concurrent algorithms and present an implementation of that idea comparing with a more common alternative.

I have a feeling that this may be something well known by people who have experience with concurrent algorithms, but since there is a chance that I’m not the only person oblivious to this idea I’m going to try and explain how I discovered it and then had some fun with it and how I think it now helps me, in some cases (it is not a silver bullet), to write simpler concurrent code.

The first time that I read about the idea of multiplexing channels in Go was in Russ Cox blog post My Go Resolutions for 2017, it was a very brief mention in the section regarding generics in Go (no, there is no way I’m not going to touch that subject here =P):

Personally, I would like to be able to write general

channel-processing functions like:

// Join makes all messages received on the input channels

// available for receiving from the returned channel.

func Join(inputs ...<-chan T) <-chan T

// Dup duplicates messages received on c to both c1 and c2.

func Dup(c <-chan T) (c1, c2 <-chan T)

I thought it was an interesting example of generic algorithm, so it stayed in the back of my mind, but I was not able to come up with an application to the idea (to be honest I did not even try too hard, I just kinda thought it was a cool example).

So I moved on with my life, and while I was reading some papers from the Inferno operational system I ended up stumbling on the language Limbo, not quite stumbled because the language used to program on top of the operational system is Limbo (it would be as C is to Linux, or even Plan9). There is no amount of words to express how awesome the whole ecosystem of the Inferno operational system is and I barely scratched the surface of the ideas, but when I was reading about concurrency in Limbo and thinking on how similar it is to Go I stumbled again with multiplexing (or joining).

From The Limbo Programming Language:

8.2.9 Channel communication

The operand of the communication operator <- has type chan of sometype.

The value of the expression is the first unread object previously sent

over that channel, and has the type associated with the channel.

If the channel is empty, the program delays until something is sent.

As a special case, the operand of <- may have type array of chan of

sometype. In this case, all of the channels in the array are tested;

one is fairly selected from those that have data.

The expression yields a tuple of type (int, sometype ); its first member

gives the index of the channel from which data was read,

and its second member is the value read from the channel.

If no member of the array has data ready, the expression delays.

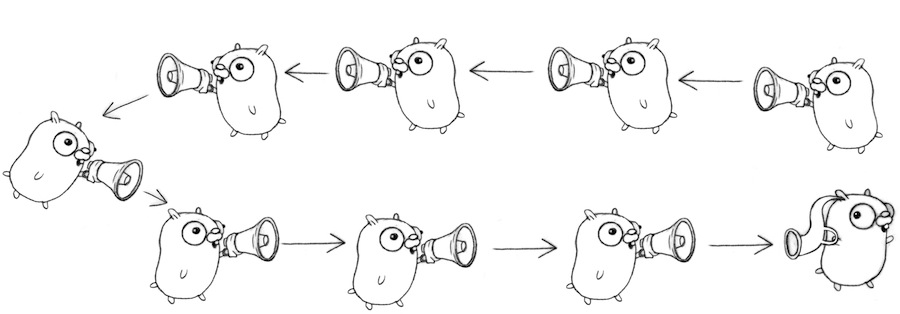

Even the communication operator is the same, but then a crucial difference, there is a special case to handle arrays of channels which does exactly the joining/multiplexing of channels. This idea seemed important enough to be supported by the language itself. I connected this with what I have read previously about joining channels (duh) and started to get strong feelings that this could be something useful when I needed to add concurrency to Go code.

As luck would have it, just as I was toying around with this idea I had a problem that seemed that could benefit from it (or I had a hammer and saw a nail, who knows ? =P). This led to the development of a small muxer package. But before I get into the specifics of the muxer package let me try to explain into small steps the applicability of multiplexing channels for at least one kind of concurrent problem, the fan-out / fan-in.

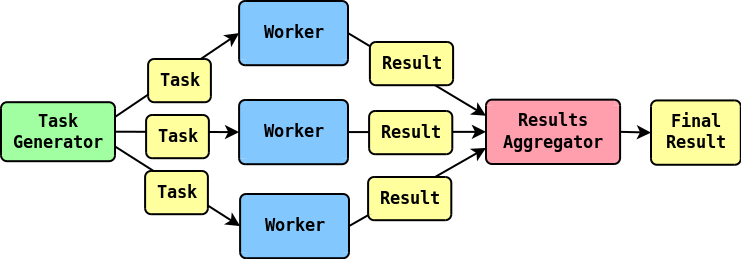

Fan Out / Fan in

The solution space for concurrent algorithms design is pretty vast, but one way to solve some problem concurrently is to set a fixed set of long lived concurrent units, that will act as workers, distribute tasks to them and then aggregate the results.

Usually in a scenario like that you have three concepts in play:

- Task generation

- Task execution

- Results aggregation

This would look at something like this:

As I mentioned earlier, the design space is vast, you can even work with a shared map and use some locking mechanism around it, but for the sake of brevity I will focus on how to model this problem using only channels and explicit communication between the concurrent units.

The fan-out part is usually easy, specially if generating a task is fast when compared to executing the task, in this case you can have a single task generator goroutine writing to a channel and multiple workers reading from it, Go is designed to make it easier to have a single writer and multiple readers, and it provides a way embedded on channels to indicate that processing is over, the close function, which makes signalling that there are no more tasks to execute trivial.

To understand how easy is to model things when there is a single writer on a channel let me introduce the sample code that we will be working from now on:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

type Task int

type Result int

func startTaskGenerator(start int, end int) <-chan Task {

tasks := make(chan Task)

go func() {

for i := start; i <= end; i++ {

tasks <- Task(i)

}

close(tasks)

}()

return tasks

}

func startWorker(tasks <-chan Task) <-chan Result {

results := make(chan Result)

go func() {

for task := range tasks {

results <- Result(int(task) * int(task))

}

close(results)

}()

return results

}

func resultsAggregator(results <-chan Result) {

sumSquares := 0

totalResults := 0

for res := range results {

fmt.Printf("received result %v\n", res)

sumSquares += int(res)

totalResults += 1

}

fmt.Printf("total os squares received: %d\n", totalResults)

fmt.Printf("sum of squares: %d", sumSquares)

}

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

results := startWorker(tasks)

resultsAggregator(results)

}

This is a concurrent sum of squares algorithm where the worker is responsible for calculating squares while the results aggregator will sum all the squares. The names are kept generic, like startWorker, to make it easier to explain the fan-out/fan-in idea and its steps.

Usually all of these steps, task generation, execution and result aggregation, are more complex, so having as little as complexity as possible from the concurrency control is a big win. At least in my opinion it does not get much simpler than that. Understanding the logic and how the computation ends is pretty simple when we leverage the close function and channel iteration.

When just 3 concurrent units are enough for your problem this is bliss, it forms a very simple concurrent pipeline. The problem is that sometimes the task execution takes more time than the other phases in this pipeline, which brings us back to the fan-out.

I wanted to start with a simpler version of the problem because the beauty of multiplexing channels stems from keeping this same simplicity but for a more complex problem, the fan-out.

Let’s say that now we want 30 concurrent workers. With the previous design that is not quite possible because we would have something like this:

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

results := startWorker(tasks)

// how to handle N result channels ?

}

resultsAggregator(results)

}

Which usually evolves to something like this:

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

results := make(chan Result)

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

startWorker(tasks, results)

}

resultsAggregator(results)

}

Which has nothing essentially wrong with it, but will not work without some further redesign on the startWorker function and the overall concurrency control.

Why is that ?

Sharing read channels is fun, sharing write channels is not

Sharing read channels is very simple, all our N workers will read from the same channel, competing to get tasks, and when the taskGenerator finishes it will close the channel notifying all the workers that there is no more work to be done, so far so good.

The disadvantage of this design is that sharing write channels is not as fun as sharing read ones. Why? Because you have to be very careful when you close a channel that has multiple goroutines writing on it. Reading from a closed channel is valid and a idiomatic way to understand that no more messages will be received on that channel, writing to a closed channel is a programming error and results in a panic.

You will need to use some synchronization mechanism to know that all workers have finished and no more writes will happen and then you can close it. Not implementing this properly can result in very sad non-deterministic panics.

If you try to avoid closing the channel altogether, you are left with the problem of notifying the resultsAggregator that the computation is over so it can properly finalize itself.

For example, let’s play with the idea of having a shared write channel and not closing the channel:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

type Task int

type Result int

func startTaskGenerator(start int, end int) <-chan Task {

tasks := make(chan Task)

go func() {

for i := start; i <= end; i++ {

tasks <- Task(i)

}

close(tasks)

}()

return tasks

}

func startWorker(tasks <-chan Task, results chan<- Result) {

go func() {

for task := range tasks {

results <- Result(int(task) * int(task))

}

}()

}

func resultsAggregator(results <-chan Result) {

sumSquares := 0

totalResults := 0

for res := range results {

fmt.Printf("received result %v\n", res)

sumSquares += int(res)

totalResults += 1

}

fmt.Printf("total os squares received: %d\n", totalResults)

fmt.Printf("sum of squares: %d", sumSquares)

}

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

results := make(chan Result)

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

startWorker(tasks, results)

}

resultsAggregator(results)

}

Which will result in:

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan receive]:

main.resultsAggregator(0x4320c0, 0x4320c0)

/tmp/sandbox287862370/prog.go:33 +0x100

main.main()

/tmp/sandbox287862370/prog.go:48 +0xa0

Because we avoided the problem of notifying the resultsAggregator that there will be no more results.

Now let’s try to make this code work properly, the space for solutions here is considerable, let’s try an approach where the resultsAggregator remains unchanged, which can only be achieved by closing the results channel:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

type Task int

type Result int

func startTaskGenerator(start int, end int) <-chan Task {

tasks := make(chan Task)

go func() {

for i := start; i <= end; i++ {

tasks <- Task(i)

}

close(tasks)

}()

return tasks

}

func startWorker(tasks <-chan Task, results chan<- Result, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

go func() {

for task := range tasks {

results <- Result(int(task) * int(task))

}

wg.Done()

}()

}

func startResultsCloser(results chan<-Result, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(results)

}()

}

func resultsAggregator(results <-chan Result) {

sumSquares := 0

totalResults := 0

for res := range results {

fmt.Printf("received result %v\n", res)

sumSquares += int(res)

totalResults += 1

}

fmt.Printf("total os squares received: %d\n", totalResults)

fmt.Printf("sum of squares: %d", sumSquares)

}

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

results := make(chan Result)

wg := &sync.WaitGroup{}

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

startWorker(tasks, results, wg)

}

startResultsCloser(results, wg)

resultsAggregator(results)

}

Which does work fine. This is usually how I would solve this kind of problem before thinking about multiplexing. There is nothing wrong with this solution but it always felt to me that it was more prone to bugs because you have this extra synchronization using the WaitGroup. Nothing against WaitGroup, but the whole solution always felt a little complex and error prone.

The ideal solution for me is the one that we got when we had only one worker, there is a symmetry and simplicity in it that is appealing to me, what if we could scale from one worker to multiple workers with the same design ?

Enters multiplexing

I made a suggestion before where scaling to multiple workers would involve just handling N channels instead of one, like this:

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

results := startWorker(tasks)

// how to handle N result channels ?

}

resultsAggregator(results)

}

But how to enable this ? If we have a channel multiplexer that transforms N channels in a single channel we can achieve it.

I went ahead and did the only thing that usually helps me understand something, trying to build it, this is not always possible (sadly), but in this case it seemed simple enough.

You can checkout the muxer code here (it even has some docs ).

As can be seen on the code, most of the logic is related with the hardships of trying to build safe generic algorithms in Go, it is indeed not very fun (although in Go defense that was the only time I needed this in like 5 years of Go programming).

The logic is pretty simple but at the same time I would not like to reimplement this for every different type that I need, so in the end I felt considerably good with the final result. It was not as good as with parametric polymorphism and not as good as Limbo which provides syntactic/semantic support to it directly in the language but it was good enough.

Now that we have a channel multiplexer, we could go on and use this idea to scale to multiple workers with no change in the overall design. I say no change because the three concepts involved in the solution remain unaltered and simple, the only change is in the coordinator (in this case main) and even there the change is minimal:

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

results := []interface{}{}

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

results = append(results, startWorker(tasks))

}

muxedResults := make(chan Result)

muxer.Do(muxedResults, results...)

resultsAggregator(muxedResults)

}

As you can see the changes on the code compared to the original design that had one worker is minimal. There is only one place of the code that is aware of the multiplexing, the rest of the design is oblivious to it and retained its simplicity.

I would not advocate for the design of the muxer package itself, it was the first idea that came to my mind at the time, but the idea is certainly worth attention. One sad side effect of the current design of the muxer is that the array of result channels needs to be declared as an array of empty interfaces (there is considerable runtime type checking to avoid a panic).

But this is more related to the design of the muxer itself than the idea (there are probably better designs, this one is pretty lazy).

Here is the whole code that you can use to check if this actually works:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/madlambda/spells/muxer"

)

type Task int

type Result int

func startTaskGenerator(start int, end int) <-chan Task {

tasks := make(chan Task)

go func() {

for i := start; i <= end; i++ {

tasks <- Task(i)

}

close(tasks)

}()

return tasks

}

func startWorker(tasks <-chan Task) <-chan Result {

results := make(chan Result)

go func() {

for task := range tasks {

results <- Result(int(task) * int(task))

}

close(results)

}()

return results

}

func resultsAggregator(results <-chan Result) {

sumSquares := 0

totalResults := 0

for res := range results {

fmt.Printf("received result %v\n", res)

sumSquares += int(res)

totalResults += 1

}

fmt.Printf("total os squares received: %d\n", totalResults)

fmt.Printf("sum of squares: %d\n", sumSquares)

}

func main() {

tasks := startTaskGenerator(1, 100)

results := []interface{}{}

for i := 0; i < 30; i++ {

results = append(results, startWorker(tasks))

}

muxedResults := make(chan Result)

muxer.Do(muxedResults, results...)

resultsAggregator(muxedResults)

}

Simplicity is the art of hiding complexity

Even tough I advocate that the overall design and code is simpler than the alternatives, this is only true if you ignore the complexity that is hidden inside the muxer. This kind reminds me of a great presentation from Rob Pike, Simplicity is Complicated.

In the presentation he talks about how simple the interface with concurrency is in Go (three keystrokes and you start a goroutine), but under the hood making that work is quite complicated.

Discovering channel multiplexing gave me a similar feeling, I hope it may be as useful to you as it has been to me.

Notes

Thanks to Jhuliano Skittberg Moreno, Manoel Vilela and Claudinei Callegari for reading drafts of this.

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email