Why Go ?

Details on the thought process of adopting Go

For me it makes no sense to talk about why a decision has been made without any context. So I will try to give some context on what was happening when we decided to give Go a shot.

We started to work at Neoway with the Go language for a year and a half right now, and on this post I will try to pass on some of the experience of learning Go.

By no means this is a representation of the experience of everyone at Neoway, there is a lot of teams working with Go. This is a very narrow and personal view on how was to me the process of learning and developing Go code.

Our team is responsible for capturing data on the web. So we basically develop scrapers and all services required for the scrapers to work properly. Right now I will focus only on the services providing support for the scrapers.

It was 2015, the second quarter, and we had something like 200 scrapers already developed on a engine that was really hard to maintain.

Why it was very hard to maintain ? The usual:

- lots of bugs

- no ones understands the code

- no tests

- no clear thought about design on the code

- strong coupling with the database

- sadly even the DSL used to write the scrapers is coupled on the database

We basically had what is described on this talk by Robert Martin, but not the good side, the bad side. There was no clear architecture and service boundaries, everything was floating around the database. Besides the obvious disadvantage of being very hard to understand (concepts like scheduling and storage were all mixed up there) we got hit by a even harder problem, the database was not scaling well anymore, this was the trigger to start a new architecture that would have clear boundaries/services and would have to scale just as the needs of the clients was scaling.

This little history is the reason why I work at Neoway, I got hired there exactly to help with this work. So we had a lot of cool choices to make, how the new scrappers where going to be developed and how the services around them would be developed.

To scrap data from the web we decided to use Scrapy, which uses Twisted to handle the heavy I/O based workload without requiring a ridiculously amount of threads to enable high concurrency. I wont get in much detail on these right now, but if you are interested they are fairly well documented.

The services that we needed to develop were:

- Proxy providing

- Captcha breaking

- Storage for the scrapers (where raw data is saved so we can trace parsed data to original raw data)

- An adapter between the new architecture and the current one

For all services around the scrapers we decided to use Go, and that the history that I’m going to tell here.

Why Go ?

As you can see, our scrapers are developed in Python, and Python has a lot of useful tools not only to crawling but also parsing (we parse all kinds of things that the web throws at us, like PDFs and SWF files). Well, as I said before, we have to maintain other services that are required for the scrapers to work properly, and since we are on a architectural migration (more on that on future posts, I think) there was a lot of new services to be developed.

So we are not thinking on developing scrapers in Go (although that sounds like fun :-)), but was aiming at these other services (spoiler alert: in the end almost all services on our data pipeline are written in Go).

Having made that clear, why Go ? Here goes a list of things I thought to pretty cool about Go.

Great performance

This one may seem like some kind of premature optimization, all that talk about how you should not care with performance, only solving your problem fast, etc (oh the joys of the tradeoffs on delivery speed and software speed) does not make that much sense when you literally pay for your computing power hourly.

If you can be 10x times faster, there is a fairly good chance that you will spend 10x less money. This has always been true, I think the cloud model only makes it even more explicit, specially as you start working with elastic infrastructure (but even on the pre-cloud era it was smart to think about that, instead of just making stuff to work, take a look on the great book Release It for more on that).

Of course this has to be balanced with good abstractions, or we would be developing everything in C until today (it is fun, but not very fast, specially if you intend to your software to work properly :-)). Go seems to match these two things very nicely, I heard a lot of cases from people migrating from Python and Ruby to Go and getting huge improvements on performance, and still being able to develop software fast, thanks to a mix of well chosen abstractions and performance concern.

A great example on how Go tries to hit a nice spot on this is the balance of being garbage collected but allowing you to have a great control on how much garbage you generate, improving your collection cycles. This is very different from most languages that puts you on a level of abstraction that is so high that you have almost no idea of what is happening with the memory.

Stupidly simple deployment

As someone with C background, but that also have experience with interpreted languages like Python, Javascript (NodeJS/Backend stuff) and Lua, I value a lot the model of just copying a binary and running it.

I worked with these interpreted languages on the more harsh and odd places, think about inhospitable environments, where there is no life and fun :-), like old kernels where proprietary crappy packaging systems were the norm. It was hell and the stuff that I had to do just to get shit working takes my sleep at night (not literally of course, I love drama :-)).

To be honest, even in C it was a hell because of dynamic libraries, but even that Go got right, it is completely static, and it has a compile mode that even the libc was embedded on the binary. It was the glory of the simplicity on deploying something (although the libc used on the compilation must be compatible with the kernel where you are going to run your binary, there is still a runtime dependency to satisfy on this case, the kernel. But it is a lot less than lots dynamic libraries).

The addition of libraries (static and dynamic) is fairly new on Go (it even got dynamic loading, yaaay the joys of dynamic loading), but when we started with it they did not even existed (and for me it was perfect that way).

Batteries included

Pretty much the basic you will need to develop services and test code. Stuff like:

- http (and http2)

- json

- testing

- profiling

- formating

- static analysis

Since go even provide libraries to help you parse Go code there is a lot of cool third party static analysis tools.

In my opinion Go hits a very nice spot of having batteries included but not too much batteries :-), and the batteries are really small, and cool, and gives you control and the choices on how to use them instead of trying to force you to work on the way they want.

Static Typing with Interfaces

I just got fascinated on how Interfaces are implemented on Go. The idea of not requiring an object to directly know and import/extend an interface to implement is the glory of dependency inversion to me.

This is not new, since it is what dynamic languages are doing for a long time, which is duck typing. Go has duck typing with static validation of your ducks, if they are quacking properly, etc.

You can have good tests to aid you on the dynamic language, but I never heard anyone complaining because a static analysis helped them identify a problem really fast with no development effort required even before the test phase.

Also this aspect of Go helped me think more about services and protocols inside my Go code, instead of thinking on objects. Basically because for me interfaces have nothing to do with objects, they are a mean to express a protocol. The struct is just a way to compose multiple functions to implement that protocol.

Go does that by not using types to validate anything, it is truly protocol oriented.

Simplicity

This is the greatest reason for me to like something, simplicity. Simplicity on the terms of:

- Only one way to do stuff

- Being explicit

- Being consistent

- As few primitives as possible

- As few abstractions as possible

Of course, enabling you to write solutions to difficult problems without imposing overheads on you. C for example has almost no abstractions, if you need to express abstractions it is not trivial to do that and requires a lot of attention to detail.

The idea is not “no abstractions”, but only the minimum required to solve problems elegantly. A good example is Lua, where almost everything is represented as tables. A module is just a function that returns a table mapping names to functions (or anything you want, modules can even just return a boolean if that makes sense to you).

There is a abstraction on this, but it is very simple, and you can still do everything (and more) that you used to do with languages that have more abstractions (like Python and Javascript, for example).

Even the global namespace in Lua is just a table, so doing fun meta-programming stuff is explicit and trivial (although not a good idea on most cases).

The idea here is not to focus on Lua, but it is another language where simplicity is beautifully expressed.

So the idea of having less abstractions is having the necessary to solve complex problems, not the absence of abstractions. In Go, good examples of simplicity are:

- Object model focused on composition and behaviour, not type hierarchies.

- Errors are just values, instead of exceptions

- High order functions, instead of decorators

- The defer statement as an easy way to release resources

- Very explicit way to do stuff (example is the error handling, but it is everywhere)

- Usually only one obvious way to do stuff

- The concurrency model

It is interesting that this kind of simplicity is also reflected on the thickness of the manual. A quote from Five Questions about Language Design:

And it's not only programs that should be short.

The manual should be thin as well.

A good part of manuals is taken up with clarifications and reservations and warnings and special cases.

If you force yourself to shorten the manual, in the best case you do it by fixing the things in the

language that required so much explanation.

The first thing that came to my mind was my last experience with Python and generators (having fun with twisted). From the PEP 255 Simple Generators

Restriction: A yield statement is not allowed in the try clause of a

try/finally construct. The difficulty is that there's no guarantee

the generator will ever be resumed, hence no guarantee that the finally

block will ever get executed; that's too much a violation of finally's

purpose to bear.

Hmm… not so simple after all these generators :-(. What seems to be happening to me here is the usual problem of having too much possible control flows on the language. It is already more complex to have more than one flow on your program (yes exceptions, I’m looking at you, fancy goto’s with even fancier switch cases), but now you have the 3 ways you can compose these different control flows (Sequential + Exceptions + Generators yielding). On this particular case the addition of generators on Python caused some problems with the previous decision of having exceptions.

Of course, you can just read the manual, but the idea is to have short programs and short manuals. Possibly there is some cases where exceptions will seem like a good idea, and the same goes for generators (we use generator a lot to develop twisted code that looks sequential, it seems better than a callback hell).

The wisdom is to think in alternative solutions to problems that these approaches solves and measuring if the complexity that these will bring to the language really pays off (not advocating that exceptions or generators are no useful at all, but questioning if they are really able to pull their weight).

In my opinion, Go achieves that pretty well. And an interesting decision is that neither of these concepts are present on the language design.

The who and why

It has been a lot of years since Go got my attention, and it started mainly with the Less is exponentially more post from Rob Pike. It was basically a group of awesome experienced developers trying to build a tool that they could use on their day to day job.

I liked was that they had a real problem to solve with the language, and a very clear public audience, that included themselves. Again from Five Questions about Language Design:

If you look at the history of programming languages, a lot of the best ones were languages designed for their

own authors to use, and a lot of the worst ones were designed for other people to use.

I read some posts talking that Go is aimed at bad programmers, because it is too restrictive. I always thought that about Java, but never from Go. It just does not seems like that. The language does not seem to be trying to restrict me, it is just trying to be simple.

Java is just not simple, and does not allow me to do a lot of stuff because it assumes I’m stupid. Go does not have a lot of stuff not because it thinks you can’t program well with them, it just thinks they are not necessary (less is more).

It is beautifully clear on the design of the language that they are people very close to the C language, but that wants some abstraction to make things easier and a concurrency model that is a first class citizen of the language.

Some things that are simple and empowers the developer:

- The interfaces model

- Control of how much garbage on the memory you are creating with your code

- Concurrency model that is expressive but gives you total control to generate deadlocks and races

Compare for example the explicit Go concurrency model, that enables you to design a concurrent system, with Java synchronized methods, that for me represents “I have no idea of what is wrong with this messy multi-threaded stuff, so let the must lock all this stuff up”. That is not truly simple and it assumes you are stupid and have no idea of what you are doing.

Given that, it really does not seem like the designers of Go where just thinking about dumb developers that have no idea of what they are doing. Go is extremely aggressive on not copying stuff around, I even had some troubles with that for being so used to program in Python and other high level languages. So the thought that Go is trying to prevent me to making mistakes do not makes too much sense. It just tries to give me all the control, as simple as possible.

Of course, good design is a design that fits well its users. And the who are the users of Go ? Well, as I understand it, the target is system programmers, that have to work on relatively big code bases. And it is system programming on the level that performance and concurrency is extremely important, but they are complex enough to be pretty hard to express in pure C (which has a totally different purpose). This explain a lot, like the control on how much garbage is generated on the memory (that can cause huge latency because of garbage collection).

The only moment that I saw Go being opinionated is on code formatting. The community tries to make code as uniform as possible. A reflect of that is that the gofmt tool only formats the code on one way and that is it.

When I was younger I would not like that, you have to respect all those people that like spaces more than tabs.

Now that I’m older… Honestly ? Fuck respect for freedom (I had my share of spaces VS tabs discussions), make the code be consistent and uniform. I don’t like tabs, yet in Go I use tabs, and if all code will have tabs and reading code will feel the same when I cross projects boundaries it is a win big enough to make me waive away my freedom to choose formatting.

But even on that matter, you are not obligated to format your code that way, and it is the only thing that I believe Go tries to impose anything, besides that you pretty much have a lot of control on how you can get things done.

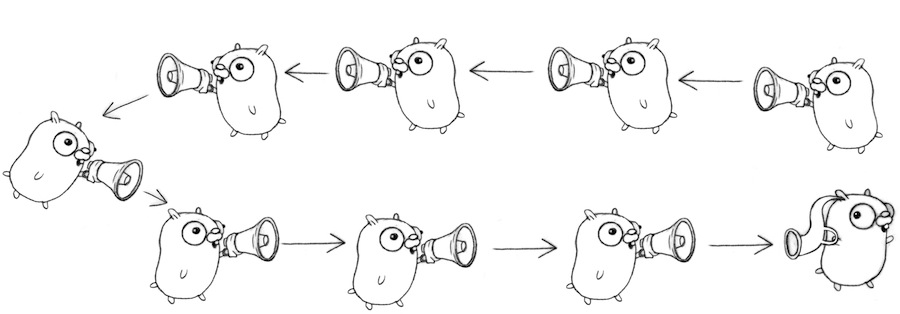

And of course, concurrency :-)

This one is the last one on purpose, because it is the more obvious one, and in my opinion people usually get overexcited with the concurrency model, leading to an overuse of it (which is the common pattern to every time you found something cool :-). But I really tried to not let myself go by the concurrency stuff, almost all our code make very little use of it, just because it is not necessary yet.

Go’s concurrency model is based on CSP (Communicating Sequential Processes), and is the best concurrency model I worked until today. Ok, I haven’t worked with a lot of concurrency models, basically traditional multi-threading and asynchronous main loops (glib in C and NodeJS).

Asynchronous main loops exploit the fact that heavy I/O loads do not need a lot of CPU time and threads, and that makes sense. The problem is that handling asynchronous code is simply harder than sequential code, you just have to think about callback pyramids of hell and other stuff. I used a lot the async module for NodeJS and there is a great movement on Javascript toward having promises and coroutines/generators/whatever-they-call-it that can make asynchronous code read more like sequential code. I think this pretty much makes the case for sequential programming as more easy to understand.

Go tries to bring the best of the two worlds. It will create multiple threads if necessary, and if you dont take care on how you code you will have race conditions. But if I/O is required, Go will optimize the I/O load to avoid making a lot of threads idle waiting for some I/O response. So you can create a lot of go routines waiting for some I/O without worrying that it will create a lot of threads that will be dumbly waiting for some system call.

This is possible because Go provides a higher level of abstraction that is not directly system threads. Actually, at least in my opinion, this is the awesome part of any concurrency oriented language. The more traditional languages that we are used, like Java, C++, C, Python and Ruby, are sequential languages that where not conceived with concurrency as a first class citizen. Sequential is the law, and concurrency is just throw up at you with threads and some hardware low level mechanism to avoid mayhem on the memory. On this case, concurrency is an afterthought. On Go it is a first class citizen, the language was built for it, from scratch.

For this, I have to quote the Communicating Sequetial Processed from Hoare:

This paper has suggested that input, output, and

concurrency should be regarded as primitives of programming,

which underlie many familiar and less familiar

programming concept

It is exactly what Go tries to achieve with goroutines and channels (although the paper reminds me more of the Erlang concurrency model than Go).

In the end, concurrent algorithms are hard. Go makes it easier, but it is still hard. It is a good idea to avoid creating lots of goroutines if you dont have proof that they are needed. And sometimes even the more high level abstractions wont cut it, as can be seen here.

Enough why, lets talk code

Since this post is already pretty big, I’m going to talk about the experience of developing the first services in Go and the bad and the good on a next one, or this one would get dangerously big.

I focused a lot on why here because a decision like that must be well based, I dont like the idea of using something just because it is trending an there is a lot of fancy conferences about that.

ACKs

Special thanks for my friends that helped me reviewing my lousy English:

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email